A few years ago I began to take my food choices seriously. Essentially, I realized my own culpability in supporting a system of cheap food production in the United States that I learned was deeply unethical, in terms of animal suffering, labor rights, the environment, and health. My sense is that many are coming to similar conclusions, which has spawned a variety of food movements across the United States and globally. Like others, my main project was meat, though I never saw the consumption of animals as inherently unethical. Not being able to afford what I considered “good meat” as a college student, I decided to stop eating it altogether.

During this period of struggle over what it meant to me to be a moral being in the contemporary United States, I converted to Islam. I had been studying Islam academically for some time, and felt drawn to what I perceived as a holistic worldview and strict, but accessible, self-discipline. Both my food choices and religious choices were connected; I was trying to live the best way possible, attempting to do the least amount of harm, and seeking guidance to make sense of what all of it meant. I’ve written more about this process in another blog post. A friend introduced me to someone he knew who also talked a lot about food ethics; Nuri and I started Beyond Halal (and got married, but that’s a different story).

Beyond Halal is a web-based project with several purposes. First, it’s where we explore the Islamic legal and ethical traditions as they relate to how humans should interact with animals. It’s a place where we can highlight our successes and failures in this area, and ultimately raise awareness within the Muslim community that our food choices matter. Like other food movements we argue that these choices impact the welfare of animals, the environment, the rights of workers, and certainly our health. What Islam, and perhaps religion in general, uniquely offers to the conversation about food ethics is a spiritual tradition that insists that food also has a subtle effect on the soul. We believe that eating meat that is ritually impure has a negative effect on our spiritual state. Additionally, Muslims strive to do the most amount of good and cause the least amount of harm in this life. In the area of food production, it is easy to forget or ignore this last part simply because we do not see where our food comes from.

Halal is the Arabic term used to designate something as permissible. When used in the context of food, it typically refers to meat that has been slaughtered a particular way, and that contains neither pork nor alcohol. Similar to kosher slaughter, halal slaughter requires that the animal’s throat is swiftly cut while the name of God is invoked. While this is the bare-bones legal definition, there are a number of other recommendations that are drawn from the stories of the Prophet Muhammad and his companions that typify our ethics in relation to animals. From numerous “hadiths” we learn that an animal should not be dragged to slaughter, but walked. They should be given water. They should not see other animals slaughtered. They should never see the knife, which should be razor sharp. The animal should be put at ease. Death must be quick and as painless as possible. In Islam, animals are an important part of God’s creation, and we know from the Qur’an that animals have their own communities and languages, and that each is engaged in constant praise of God. From other hadiths we learn that animals should be treated kindly and with respect; cruelty towards a cat is what literally sends one woman to hell.

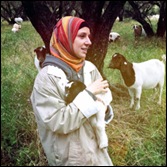

I’ve started eating meat again over the past year, which has been in many ways and on many levels a process of discovery. We’ve identified a number of farms and businesses in the United States, Canada, and the UK that raise and slaughter their meat in accordance not only with the legal principles of Islam, but with deep respect for its ethical principles. Slowly, these Muslim (and Jewish) companies and organizations are showing us that religion, quite literally, has something to bring to the table.

No comments:

Post a Comment